Sagarmatha Next ©Tommy Gustafsson

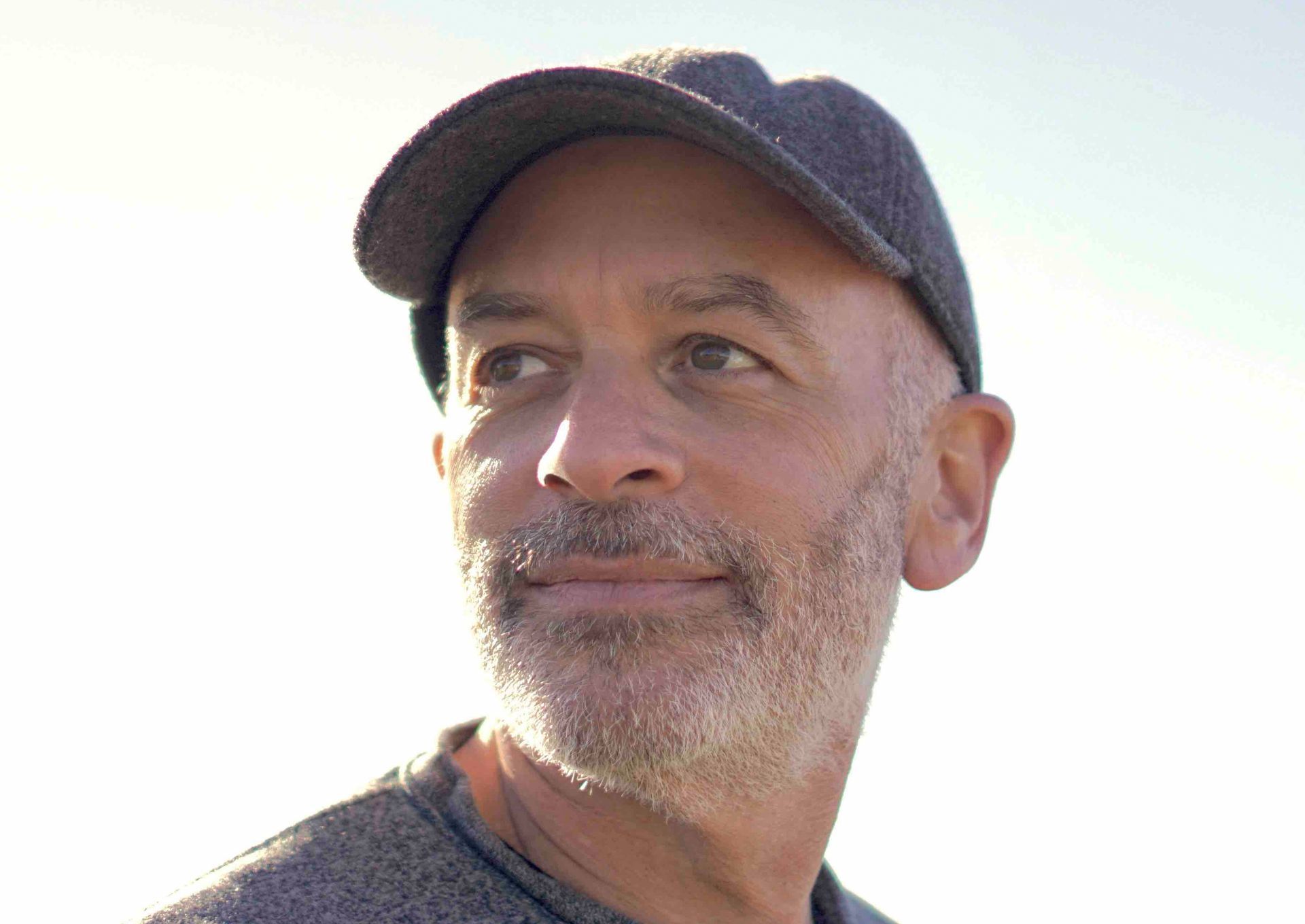

Tommy Gustafsson: “Would they be willing to make a small contribution and carry a one-kilo bag of crushed plastic bottles?“

Tommy Gustafsson is a mountaineer, former CEO of sports marketing companies and founder of Sagarmatha Next, the world's highest museum. He and his co-founders develop highly innovative environmental concepts such as the Carry Me Back programme and have been able to recycle more than 25 tonnes of waste in the last two years.

After decades of travelling to the region as a mountaineering tourist, Gustafsson became determined to solve the huge problem of pollution in the Sagarthama region, the national park where Mount Everest is located. Together with two friends, they embarked on a major endeavour not only to build a museum in the middle of the national park, but also to develop complex concepts to solve the waste problems of the entire region. The museum, which he describes as a showcase, is now the headquarters from which Gustafsson and his team operate. An important component of the project is the ingenious Carry Me Back programme, which was developed after years of analysis and which specifically means that each participant takes 1 kg of recycled waste with them from the region to the collection point in Lukla, where the only airfield is located. The founders also face the huge task of introducing a waste separation system throughout the region. Moreover, one of the biggest sources of plastic waste are water bottles, as people have to drink four or five litres of water a day to get used to the altitude.

The museum itself has already attracted over 38,000 visitors in its second year. Artists are selected who deal with environmental problems. The museum is doing so well that artists are surprised at the high sales figures. The museum exhibits small works of art as well as large sculptures and also produces souvenirs from recycled waste.

We recently reported on New York artist Benjamin Von Wong's art project on Mount Everest. He is one of the best-known artists and activists in the world when it comes to environmental art. The project is currently on display as an art installation in front of the Sagarmatha Next Museum.

————-

18 November 2024

ENVIRONMENT

Name: Tommy Gustafsson

Occupation: Co-founder Sagarmatha Next

Residence: Mount Everest

Sagarmatha Next Founder Tommy Gustafsson ©Tommy Gustafsson

AM: What is so magical about Mount Everest?

TG: I was about 7 years old and read Tintin's adventures travelling to Tibet and Mount Everest. I had the idea early on that one day I would like to go there too. For 30 years I have been visiting there on and off and now I have been living right next to the mountain for 9 years. Mount Everest has a special place in my heart and for the people of Nepal it is sacred in many ways and probably the most important thing that Nepal has and that the world knows. The mountain is beautiful no matter what angle you look at it from.

AM: How many times have you been to the summit of Mount Everest?

TG: Of course I had the ambition to climb to the summit. I was part of the first Swedish expedition in 1987, which started from the Tibetan side, the north side. During the summit period in May 1987, the weather was very unfavourable and we had to retreat at 8300m, about 500m below the summit. In fact, no expedition climbed Everest that spring of 1987. In 1991 we made another attempt with a Swedish expedition. Only three of our 15 team members reached the summit and we then decided to call the expedition after we almost lost one of the summiteers due to the very difficult conditions. The team were all involved in creating the route and the ascent, but only three members actually made it to the summit – but as a team we did it. After that, Everest was no longer my priority.

‘In 2011, I supported a first major clean-up operation on Everest, where we focused on the waste challenges and tried to elevate awareness of the people in the region .’

AM: The Sagarmatha Next Centre is a very large project with so many activities. How did you manage it?

TG: I have been coming to the region for over 30 years for hiking and climbing and at some point also for the human relationships. So, I knew the challenges and problems of the region. The region is very popular with visitors, with almost 80,000 visitors every year and 8000 locals, you have to bring a lot of supplies for people to live and visit there. And then the supplies become waste. In 2011, I and couple of friends supported a first big clean-up campaign on Everest where we focused on the problem and tried to make local people more aware about the waste issues. Afterwards, we sat down with a local Sherpa and another friend in Kathmandu and discussed what we could do. The question of how to deal with the large amounts of waste was a big challenge for the locals. Were the locals prepared to take on this task? You can't just come in from outside and solve the problem, because you have to support local, committed people and organizations. After two years of exchange, we developed a long-term plan for the region. Part of this was the establishment of Sagarmatha Next, a recycling show case and outreach centre aimed at both the locals, but also for all visitors who come to the region. Because when you are many and do something together, you can achieve a much greater impact and greater results. Sagarmatha Next works as an partner to support the local organization SPCC/Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee that collect, process, package and transport the waste from the region back to Kathmandu where there are factories with recycling capacity. So, we are basically a facilitator and we also support them with funding so that they have enough resources to build capacity.

‘We were three people who founded this place and I'm the one who lives up there, overseeing and coordinating everything.’

AM: Are you supported by the government or by companies, or do you have such resources yourselves?

TG: We were three people who founded Sagarmatha Next and I am the one who lives up there, overseeing and coordinating everything. My Co-Founder Sherpa friend's family provided us with the land on which we built the centre; most of the land up there is a national park. He is now the chairman of our non-profit organization. The third Co-Founder is an Indian friend and his family has a long-standing relationship with Nepal. They own a hotel group and it was a donation from their family foundation that funded the creation and building of Sagarmatha Next. From day one, our aim was to run this Not for profit distribution organization as a professional business in order to be able to be self-sustained and ensure a long term commitment.

In the last two years we have had five international artists on site and we have been able to sell almost 90% of all the artwork they have created. We don't charge admission, but we do have a donation box. If anyone feels that they would like to support our work, they can make a donation. We also make souvenirs from some of the waste materials, such as a small model of Everest. We also invite artists to our centre for a month’s residency each time. The artists are asked to use the waste to create works of art and these are exhibited in our Denali Schmidt Art gallery. There are larger outdoor art installations that attract visitors to visit our center and they also communicate our message about the need for proper waste management handling in the region. In the last two years we have had five international artists on-site and we have been able to sell almost 90% of all the artwork they have created.

Sagarmatha Next with artwork by Banjamin Von Wong ©Tommy Gustafsson

Sagarmatha Next ©Tommy Gustafsson

AM: Quite an achievement for an art gallery to sell almost all their work.

TG: Yes, I know we have been fortunate and the artists are all established artists represented by galleries in their respective countries, but they have been pleasantly surprised as they usually don’t sell most of their work in one exhibition in their home countries. We have been very, very lucky. Everything has worked extremely well. But the art is not just art, it has a story that goes beyond that. It is part of raising awareness of the challenges of waste and pollution. And it's a way of showing that waste can actually have a value if you treat it in an innovative way.

AM: The customers are then the trekkers and mountaineers and they take your objects with them?

TG: The artists usually make different kinds of artworks, some are bigger and some are a bit smaller. The largest artwork we sent out weighed 80 kilos and was two metres by one metre. We had to make a wooden holder and pack it so that it was protected and then transport it all the way back to Kathmandu from our place, which is quite complicated. But there are also people who pick up their own work themselves and bring it back.

AM: The souvenir business must work very well?

TG: Of course we hope that as many people as possible will want to support us by bringing home a souvenir, but it's not like that. We are only in our second year with two seasons, spring and autumn, and this is the fifth season. Since opening we have had almost 38,000 visitors to the centre, which we think is incredible. We’re very pleased with how it's turned out because we've been able to support ourselves from the beginning, in terms of our own operating costs. When you're a non-profit organization, we're allowed to make profits, but they have to be reinvested in the region. Basically, we donate anything over and above our own costs to the local organization that we're helping to implement the sustainable waste handling system for the whole region. So, it's quite a big undertaking to introduce a system in all those places. There are four valleys and some end at over 5000 metres above sea level. But we and our local partner organization SPCC has started the work and the process and it will probably take a few years before it has been introduced it everywhere, but we're working on it every season, every month.

AM: What is the name of the organisation you support?

TG: The organization has a long name and a short combination of letters, - the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee, abbreviated as S.P.C.C.. Sagarmatha is the Nepalese name for Everest.

‘With professors specializing in environmental issues from the USA and Nepal, we worked out a plan for implementation throughout the region.’

AM: How are your plans working - the waste management master plan and the Carry Me Back program in implementation?

TG: The first thing we did was to work with the S.P.C.C. organization to bring all the settlements together, the villages along the four valleys up to the high points. Before this project began, the locals collected waste from the paths and then took it to landfill sites where it is incinerated. When the landfills are full, they are covered up. The first thing we did was to make an inventory of all the landfills to see what type and amount of waste was being generated. With professors specializing in environmental issues from the USA and Nepal, we drew up a plan for implementation throughout the region. We sent this plan to the MRD Journal, a mountain research and development journal, which is probably the most recognized academic journal in the world when it comes to mountains and the environment. They peer reviewed our plan for nine months and then we had hundreds of questions from them. And finally they published the whole plan in their journal.

This plan, which we and SPCC are now trying to implement step by step, the ‘Carry the Carry Me back’, a solution for transporting the collected waste in this high-altitude region.

"The idea was to appeal to everyone. Would they be willing to make a small contribution and take a one-kilo bag of crushed plastic bottles, bottle caps, veiled or crushed metal cans, which make up a large part of the waste we have.“

You know, we have no roads and no vehicles here. It takes three days to walk from our village to the nearest road. Alternative routes using helicopters, porters and mules proved impractical to solve the main problem. And so we came up with the idea: wait a minute, we have 80,000 visitors, and most of them return to the place from where most people enter the valley, Lukla, an airstrip where people fly in. The idea was to reach out to everyone. Would they be willing to make a small contribution and carry a one-kilo bag of crushed plastic bottles, bottle caps, veiled or crushed metal cans, which make up a large part of the waste we have. This is how the idea for ‘Carry Me Back’ was born. The local organization SPCC runs it, but we support it both by funding the operating costs and the development of several collection points.

AM: An ingenious plan. What about the Nepalese government's regulation from 2014, which says that if you don't take your rubbish with you, you have to pay a fine of 4,000 euros.

TG: That applies to the expeditions climbing Everest. Every expedition on the mountain has to deposit 4,000 USD as an environmental deposit fee. This means that they have to declare all supplies/materials they bring into the region up to base camp. When they return, they must declare everything they bring back. Also every climber who receives a summit permit for Everest is obliged to bring eight kilos from the high camps back to base camp. The system is not flawless, of course, because sometimes people are fighting for their lives to get back down when they have already reached the summit. And if you're fighting for your life, you might not be as motivated to put another eight kilos on your back. The local organization we work with also coordinates and collects all the waste in Everest Base Camp from all expeditions. We are trying to extend our system to the mountain as well. But the first step is that you have to have a functioning system, not just from the higher camps on Everest or other mountains and the base camp. You have to have a system that works in the whole region for transportation and processing. Then you can add what's up in the mountains and what needs to go down. So it's a kind of step-by-step approach.

‘One of the biggest plastic waste is of course the water bottles, because people have to drink four or five litres of water every day to get used to the altitude.’

‘It takes time to change people's mindsets and habits, which has been going on for three or four decades.’

AM: What about waste separation, or is that too time-consuming?

That's an important part of the plan, but when we started it was a bit messed up. Basically, all waste collected from lodges, hotels, cafes, restaurants and waste bins were deposited into big landfills and later incinerated. One of the aims of the masterplan now is to encourage both businesses and local households to do an initial separation of waste, to have at least three bins, one bin for plastic, one for metals, and one for paper. But it takes time to change people's mindsets and habits, which have been in place for three or four decades. However, under the Carry Me Back program, they don't have to separate, because the bags already contain separated waste. One of the biggest plastic wastes is of course the water bottles, because people have to drink four or five litres of water every day to get used to the altitude. The visitors do not trust the water from the taps and therefore they buy plastic water bottles. When the organization collects the bottles, it removes the bottle cap and the small ring, which is made of a different plastic, as well as the label. They shred the bottles into flakes so that we can pack about 20 to 25 bottles in a one-kilo bag instead of maybe three if you pack them as a bottle. Tin cans are crushed and they are then packed in bags. The Carry Me Back system is therefore a system for the sorted transport of waste.

‘In the last two years, we have recycled more than 25 tons of waste, rather than simply sending it to another landfill site. So that's is a big step forward from zero a few years ago.’

AM: Do the Sherpas and their families separate their waste?

No, not yet. We are at the beginning of our journey, we call it, transformation process, but many locals are very positively motivated to participate in these solutions and do their small part of the responsibility, e.g. separation at source. In the last two years, we have recycled more than 25 tons of waste, rather than just sending it to another landfill. So that's a big step forward from zero a few years ago.

‘Of course it shouldn't be a private initiative that is responsible for funding waste disposal in the national park; you can't just come and say: “This is your responsibility.”

AM: Are there any political parties in Nepal that support environmental issues?

TG: Let's put it this way, waste management hasn’t been top priority in Nepal. Our project is a private initiative and we upport the local organization SPCC so that they can increase their capacity and implement a sustainable waste management system in the region.. Now the local government is supporting SPCC the local organisation with a limited budget and that's a big step because before the issue of waste management was not even on the agenda. This is not enough and so we need to raise more money. Of course, it shouldn’t be a private initiative that is responsible for funding waste disposal in the national park, but here too you have to proceed step by step, you can't just come along and say: ‘This is your responsibility. The local government is now very proud and supportive of Sagarmatha Next. When official visitors or politicians visit, they often take them to Sagarmatha Next. And the first thing they say is: ‘Look what we have done’.

‘It is a process and has no end date. It's a process where it becomes more and more natural for everyone to participate in one way or another and let the results grow.’

AM: So, my last question would be, what is your forecast for the region?

TG: The goal we have set ourselves is ‘Leave no waste behind’, in a way a utopia, to believe that in the future you will have a region with more than 80,000, maybe 100,000, 120,000 visitors and they will leave no waste behind. Then you would probably be disappointed and the most important thing is that we become more and more effective every month, every season, every year. It's a process and it doesn't have an end date. It's a process where it becomes more and more natural for everyone to participate in one way or another and let the results grow.

---------

The Carry Me Back Proggramm ©Tommy Gustafsson

TOP STORIES

ENVIRONMENT

007: Who is Paul Watson and why was he arrested?

_____________

FREEDOM OF SPEACH

Julian Assange und die Pressefreiheit. Eine kleine Chronik (DE)

_____________

DÜSSELDORF OPERA

The surprising switch of course

_____________

PHOTOGRAPHY

Without censorship: World Press Photo publishes the regional winners of the 2024 photo competition

_____________

FLORENCE

_____________

April 2024

DÜSSELDORF

Controversy surrounding the Düsseldorf Photo Biennale

_____________

WAR

March 2024

_____________

ISRAEL

November 2023

_____________

ENGLISH CHRISTMAS

10 years of Glow Wild at Kew Wakehurst.

October 2023

_____________

TRIENNALE MILANO

Pierpaolo Piccioli explains his fascination with art.

_____________

NEW MUSEUMS

29 May 2023

_____________

NEW MUSEUMS

is coming in big steps.The Bernd and Hilla Becher Prize will be awarded for the first time.

19 May, 2023

_____________

VISIONS, ARCHITECTURE

MARCH 10, 2023

_____________

CHECK THE THINGS YOU WANT TO THROW AWAY

HA Schult's Trash People at the Circular Valley Forum in Wuppertal on 18 November 2022.

NOVEMBER 19, 2022

_____________

THE OPERA OF THE FUTURE

Düsseldorf, capital of North Rhine-Westphalia will receive the opera house of the future.

FEBRUARY 15, 2023

_____________

FLORENCE

The extraordinary museums of Florence in 2023.

JANUARY 1, 2023

_____________

DÜSSELDORF

DECEMBER 11, 2022

RELATED TALKS